It has been almost 30 years since Mad Cow Disease caused a national and international panic. Mad Cow Disease (Bovine spongiform encephalopathy) is believed to have entered the bovine food chain when bones from infected sheep were ground into animal feed as a nutritional supplement. Though the resulting neurological disease caused by consuming infected beef was responsible for relatively few deaths, the panic the crisis caused had a devastating impact on farmers and their livestock. However, mad cow disease was not the first cattle plague to sweep across the country.

Rinderpest

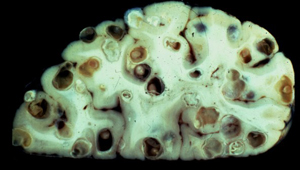

Diseases and infections were well known to farmers even before the advent of modern understanding of germ theory and immunology. Cattle plagues were a recurring feature of 18th and 19th century agriculture, with epidemics of a disease now known as Rinderpest sweeping across Britain and mainland Europe. The virus caused a high fever along with ulcers and a discharge of bloody mucus. Though Rinderpest didn’t affect humans, dairy and meat from diseased animals was not fit for consumption, and the disease had a mortality rate as high as 90%. Once infected, entire herds could be wiped out in the space of a week.

Dodging the Slaughter

Epidemics often took a long time to stamp out. For example, an outbreak in Essex and London took 13 years to eradicate. This was in part due to non-compliance with the government’s immediate slaughter policy. While some compensation was offered, it was not nearly enough to match the market value of the cows. Faced with the prospect of losing entire herds, many farmers sought to save their livelihoods as best they could, and would often gamble on their animals’ recovery instead of shooting them. Widespread falsification of certificates and papers meant that potentially infected cattle were still being transported and sold before they could be declared valueless.

Mad Cow Disease

When cases of Mad Cow Disease began to appear during the 1980s, the national response was similar to the outcry almost 100 years prior. BSE was just as severe as rinderpest had been, but it was even more dangerous because it could also affect humans. Eating beef infected with mad cow disease could lead to Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, an incurable neurological condition that caused severe dementia, including loss of motor coordination, personality changes, and blindness. Many sufferers lost the ability to walk or even speak coherently. The condition is fatal, and to this day no-one is known to have lived longer than 2 and half years after contracting it.

Although the government quickly put a slaughter policy in place, many farmers were unwilling to have entire herds destroyed as it was not clear how contagious the virus really was. By 1990, there were over 19,000 confirmed cases on almost 10,000 farms across Britain. The epidemic reached its peak in 1993 when there were 100,000 confirmed cases. In total, it’s estimated that 180,000 cattle were affected – compared to the 4.4 million cattle that were slaughtered in an effort to curb the disease.

The Wider Impact

Though the relative number of deaths was small, the main impact of the mad cow disease panic was on farmers. More farmers committed suicide from the impact of mad cow disease than the 178 deaths caused by BSE infection. Entire livelihoods were destroyed, valuable and much loved cattle lost, and the public mistrust of British beef took a long time to go away. Indeed, the EU did not lift the ban on exporting British beef for 10 years, with some countries extending the ban long after this. Though the large scale slaughter of potentially infected herds was arguably necessary, there is still lingering anger over the policy.

Sources and Further Reading

Fisher, John R. “Cattle Plagues Past and Present: The Mystery of Mad Cow Disease.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 33, no. 2, 1998, pp. 215–228

Nurse, Stuart. “The Sad Saga of Mad Cow Disease.” Alternatives, vol. 18, no. 3, 1992, pp. 9–10

Balter, Michael. “Tracking the Human Fallout from ‘Mad Cow Disease’.” Science, vol. 289, no. 5484, 2000, pp. 1452–1454

Broad, John. “Cattle Plague in Eighteenth-Century England.” The Agricultural History Review, vol. 31, no. 2, 1983, pp. 104–115