The advent of the industrial revolution at the beginning of the 19th century saw new manufacturing processes which were able to turn out products on a never before seen scale.

Arsenic was a by-product of the mining and smelting industry, and began to be produced in enormous quantities during the 1800s. Arsenic was already a well known poison, having been the weapon of choice for many murderers for several centuries. However, with the new influx of supply, people began to find other uses for arsenic, and it slowly invaded almost every aspect of Victorian life.

Accidents Happen

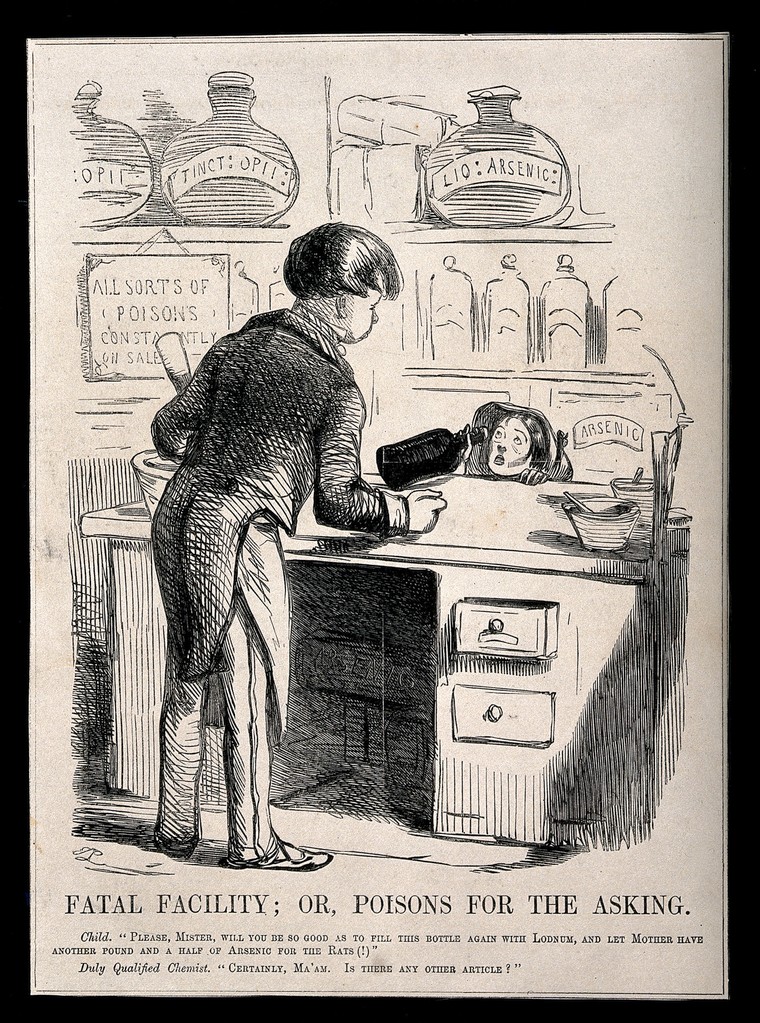

Throughout most of the 19th century, the sale of arsenic was poorly regulated, and anyone was able to buy or sell it. Arsenic was most commonly sold and used as rat poison, and due to its cheapness (half an ounce cost a penny, the same as a cup of coffee) and ready availability, arsenic could be found in almost every shop, home, and factory in Britain.

Arsenic was often stored around the home in unlabelled containers, and could be regularly found in the pantry or near other foodstuffs. However, white arsenic bore an unfortunate resemblance to a myriad of other widely used powders, including sugar, flour, chalk, plaster, and starch . Mistakes were inevitable; there are countless examples of arsenic accidentally being baked into cakes and other edibles. In the space of just two years (1837-39), there were 506 accidental deaths reported in Britain which were caused by inadvertently ingesting arsenic. Countless others were made horrifically ill, with symptoms including headaches, severe diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pains, and convulsions.

Tricks of the Trade

Accidents like this were even more prevalent when coupled with the actions of unscrupulous traders and manufacturers. The act of switching ingredients with cheaper substitutes (known as adulteration) was a common practice during the Victorian era. For example, confectioners often substituted powdered sugar for plaster of paris, which was considerably cheaper. However, in one shocking case that became known as the Bradford Incident, arsenic was accidentally used instead of plaster. The tainted sweets killed more than twenty people (including several children) and caused violent illness in dozens more.

Arsenic did not even need to be ingested in order to kill. Breathing in powdered arsenic was also responsible for countless poisonings. Makers of artificial flowers were in particular danger, as the green dye (made from copper arsenate) used to colour leaves was often rubbed onto waxed fabrics by hand. Not only did those employed in flower workshops suffer painful skin irritation, they also ended up inhaling large amounts of arsenic through the dust that was constantly diffused into the air. Those who weren’t killed by the arsenic were often forced to take extended periods of leave from work as their injuries became increasingly painful and disabling.

Everyday Arsenic

Despite the known dangers of accidental poisoning, and the well publicised examples of such incidents occurring, arsenic tainted products could be found everywhere. Perhaps the most well known use of arsenic is the use of ‘Scheele’s Green’. The colour was the height of fashion during the 1800s, and copper arsenate was found to give a much more vibrant green than other substances like malachite or verdigris. Arsenical dyes were used everywhere; not only in artificial flowers, but also in paints which were then used to colour bedroom walls and childrens toys, in paper used to wrap confectionery and cover books, and in fabrics used to make dresses, stockings, and gloves.

Copper arsenate dye was also used in wallpaper, and perhaps most famously in those designed and manufactured by William Morris. Though by the 1850s there was growing suspicion from consumers, physicians, and scientists alike that green wallpapers were making people sick, Morris dismissed the claims. As the belief was that it was arsenic dust that made people ill, and that only cheap wallpaper could flake and produce such dust, manufacturers argued that there was nothing to fear from their good quality wallpapers. It was not until 1891 that it was conclusively demonstrated that fungus in wallpaper paste would metabolise the arsenic in wallpaper and release arsenical gas; it was this gas, rather than dust, that had been covertly afflicting people for decades.

The Power of Public Opinion

The government was highly reluctant to intervene in the use and sale of arsenic, or impose any strict regulations that might have ensured consumers safety. The imposition of regulation into citizens’ private lives was seen as a violation of individual rights. Politicians, traders, and indeed many consumers felt that people should be free to buy and sell as they wished. If the public didn’t like something, they argued, they could simply stop buying it. This is precisely what they did; by the end of the century public fear of arsenic poisoning had become so great that consumers heavily favoured brands who purported to be ‘arsenic free’. Realising that consumers were finally rejecting arsenic tainted products, manufacturers followed public opinion, and the widespread poisoning seen during the 1800s became largely a thing of the past.

Sources and Further Reading

https://crosscut.com/2010/09/arsenic-victorians-secret

Whorton, JC., The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work and Play, (New York, 2010)

Haslam, JC., ‘Deathly décor: a short history of arsenic poisoning in the nineteenth century’ Res Medica, Vol 21, Issue 1, 2013