Gout is a painful type of arthritis caused by an excess of uric acid in the blood, which then builds up in the joints, causing painful swelling and inflammation. Though not typically dangerous, it can be debilitating if untreated. The condition is usually caused by overconsumption of alcohol and fatty foods combined with general inactivity.

Though gout is usually associated with the decadence of the pre-revolutionary era, the disease has been affecting people for thousands of years. The ancient Greeks observed that the malady only seemed to affect older, sexually active men, and thus associated it with those who were typically healthy, rather than people who were usually sickly. This association continued throughout the centuries, causing gout to become something of a desirable disease to have, as it was seen as a sign of a vigorous constitution.

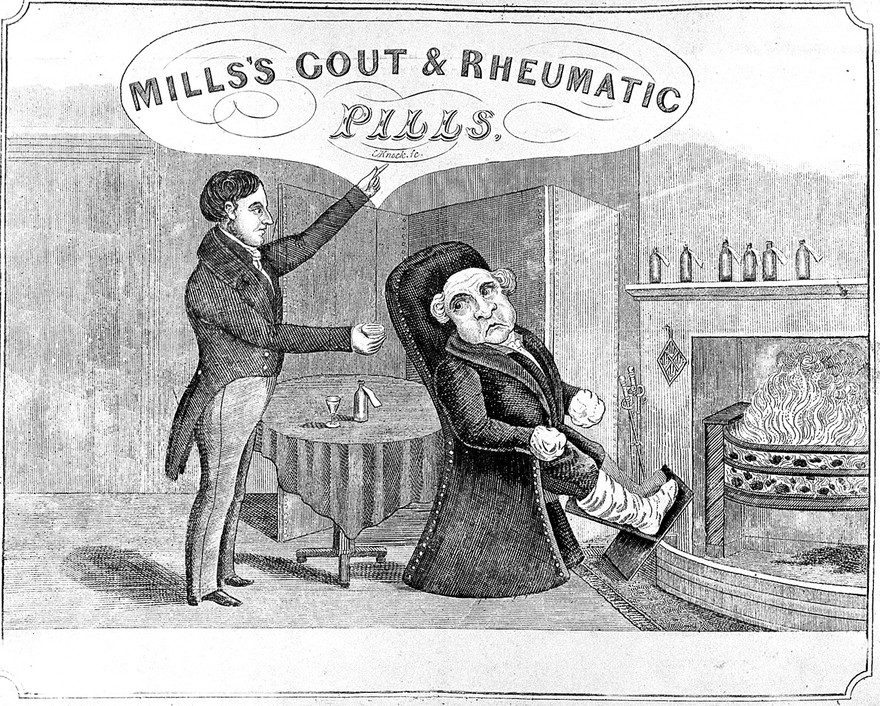

A Badge of Honour

Gout became a fashionable malady partly because it afflicted many wealthy and influential people. As well as royalty and nobility, famous sufferers included talented intellectuals like Samuel Johnson, John Napier, and Pitt the Elder. Thus the desire to be associated with the great and good made gout seem an attractive status symbol. The disease was widely believed to be hereditary, running in good families, so gout was thought to be a sign of good breeding. It was also thought to prevent other more serious illnesses, such as dropsy, apoplexy (stroke), or fevers. Gout was therefore seen not as a problem but a boon, and many people who were afflicted with gout were quite happy to endure its agonies in exchange for its supposed benefits.

Tincture Treatments

Though people were unwilling to have their gout cured, they were eager to relieve the painful symptoms. Since antiquity, the typical treatment for gout had been bloodletting, following the assumption that the ailment was caused by an excessive buildup of blood. In 1683, Thomas Sydenham, known as the English Hippocrates, wrote his own treatise on gout, perhaps because he himself was a long term sufferer. He recommended a light diet and regular doses of his own digestive remedy containing various herbs, which he dubbed ‘bitters’. The tincture became very popular, and other entrepreneurs soon began marketing their own remedies. In 1783 Nicolas Husson included meadow saffron in his mixture. The new addition turned out to be effective, and colchicum became a popular remedy. George IV famously suffered from gout among a plethora of other health problems caused by his gluttony and laziness. He rejected the more traditional treatments of his physicians, preferring to self medicate with colchicum. This royal influence helped to elevate colchicum’s status, and it soon became the remedy of choice.

A Chemical Cure

In 1776, Karl Scheele, who is best known for the introduction of the arsenical compound Scheele’s Green, isolated and identified uric acid. Over the next century, other chemists would discover the presence of the acid in the joints of those suffering from gout, and make the connection between the two. Later, it was discovered that colchicum contains the alkali colchicine, which blocks the metabolic pathway that causes the buildup of uric acid. The discovery of colchicine in the nineteenth century has remained central to the treatment of gout until very recently. Today, the condition is generally treated with non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) such as ibuprofen.

The Rich Man’s Disease?

Following the French Revolution, gout soon fell out of fashion as it came to be associated with the decadence of the wealthy that the populus had so vehemently rejected. Gout was no longer flaunted as a sign of one’s success, and instead came to be viewed as a sign of laziness and self-indulgence. Though today the disorder currently affects around 2% of people, it is starting to see something of a resurgence as people live longer, and general lifestyles and eating habits shift.

Sources and Further Reading

Barnett, R., The Sick Rose or; Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration, (London, 2014)

Porter, R., ‘Gout: Framing and Fantasizing Disease’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, (Spring 1994)