Phrenology is the idea that the shape of the head is a physical manifestation of the personality. By feeling the shape and contours of a subject’s head, phrenologists believed they could determine their overall personality, including any predisposition they might have to insanity or criminality. The theory was developed in 1796 by Franz Joseph Gall, who believed that bumps on the skull were caused by pressure from the brain, and that this could help inform assumptions about a person’s fundamental characteristics. The theory is now recognised as a complete pseudoscience, but the idea enjoyed a period of relative popularity for well over 100 years.

Well-Intentioned Ideas

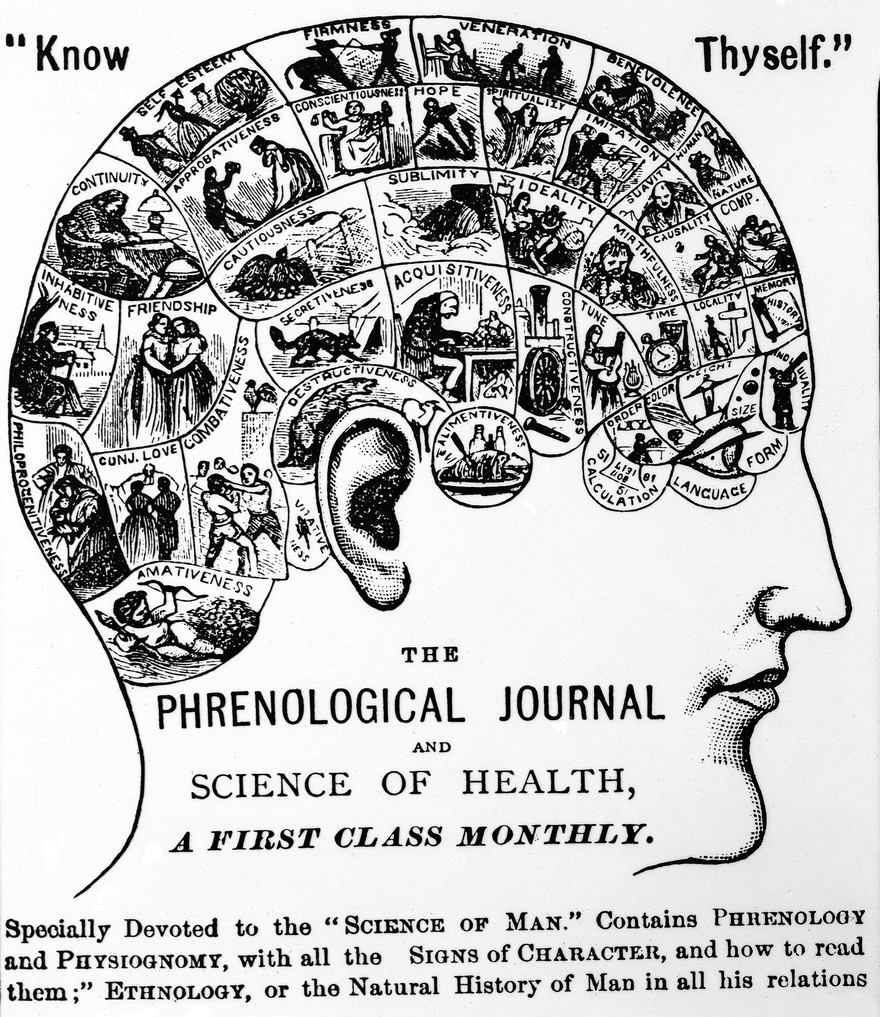

Gall believed that the brain was made up of 27 separate organs, each responsible for different personality traits, such as integrity, willpower, and intuition. He reasoned that areas that were often used and well exercised would grow larger, whilst areas that were not used would shrink, thus creating a unique topography that could be ‘read’ to determine a person’s character. The idea was popularised in Scotland and subsequently the rest of Britain by George Combe, who formed the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1820, which became the centre of the British phenology movement. At the peak of its popularity, the society had 120 members, many of whom came from medical backgrounds. Many early proponents of phrenology thought that it could be used as a basis for positive social reform, as they believed that the mind had only to be exercised in the right way in order to improve a person’s character. Many were advocates for education, asylum reform, and rehabilitation of criminals.

Popular Science

Phrenology became extremely popular in Britain partly because Combe cleverly marketed it towards the newly developing middle classes. Scientific lectures were becoming a popular form of entertainment as people hastened to find ways of making themselves appear intellectual and sophisticated, thus distinguishing themselves from the uneducated lower classes. The newly emerging ideal of self-betterment (and the benevolent betterment of the lower classes) meant that phrenology became a huge money maker for phrenologists who offered personal examinations and sold their charts and books to the nouveau riche.

However, this popularity and quick monetisation meant that phrenology soon came to be considered by many intellectuals as little more than a parlour trick, and phrenology was quickly relegated to a fringe movement within the medical and scientific communities. Interest in phrenology among scientists and social reformers began to wane by the 1840s as they drifted towards psychiatry, anthropology, and criminology instead.

Pseudoscience to Neuroscience

Although phrenology was considered a pseudoscience very early on, it was based on principles that were not too far from the truth. The idea that certain areas of the brain are connected to separate thoughts and emotions was an important step towards modern neuropsychology and the understanding of brain function. It is now understood that different areas of the brain do indeed control different things, but rather than dictating certain personality traits, the brain is divided by much more general functions such as motor skills, cognition, and perception. In 2018, a group of neuroscientists conducted a study to see if the theory of phrenology had got anything right at all by comparing thousands of MRI scans to data about lifestyle and demographic information, and cognition and language tests. They did discover some interesting associations; they found a strong link between the traits ‘amativeness’ (sexual arousal) and ‘words’. In short, they found that the more sexual partners someone has had, the higher their verbal fluency. However, overall they (unsurprisingly) found no correlation between skull contours and Gall’s personality traits.

A Theory Disproved

Ironically, it was the efforts to prove the accuracy of phrenology that ultimately led to its downfall. Early experiments that dissected and impaired areas of the brain in both animals and humans showed that the regions of the brain that Gall had originally identified as dictating certain faculties did not seem to match up with their actual functions. As more and more emphasis began to be placed on empirical evidence for scientific theories, it became apparent that phrenology just didn’t hold up. However, the theory still enjoyed some support well into the twentieth century, and continued to be used to justify racist ideologies such as eugenics until the 1950s.

Sources and Further Reading

https://archive.org/details/systemofphrenolo00combuoft/page/n7/mode/2up

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edinburgh_Phrenological_Society