Leprosy is one of the oldest known diseases, with written references to sickness that scholars suspect were leprosy dating back to as early as 1500 BC. Geneticists have traced the origins of the disease to East Africa, where it spread across the continent and then to Europe by following human movement along trade and migration routes. When leprosy became a common affliction in Europe during the medieval period, it was seen to be as much a moral affliction as a physical one, as it was often believed that those suffering from leprosy were being punished by God.

Today, leprosy (now referred to as Hansen’s Disease) is known to be caused by bacteria, and is treatable with antibiotics. Though cases of the disease do still occur, instances are much rarer and tend to be isolated to areas with tropical climates.

The Living Dead

In medieval Europe, people afflicted with leprosy were commonly referred to as ‘lepers’, and were shunned from mainstream society. They were often segregated and forced to live in colonies with others like them, many of which were run by or aided by monasteries. Though most of these church-run hospices, known as leprosaria, provided food, comfort and what medical care they could, some religious sects took a more dismal view of the disease. For example, some Catholic communities viewed leprosy as a kind of living death, and held ceremonies where lepers were declared symbolically dead; sufferers were made to lay in a grave while a priest recited burial rites over them. Lepers were not allowed to own property, and those who couldn’t find a place in a colony had to rely on begging. Famously, lepers had to ring a bell in order to warn people of their approach.

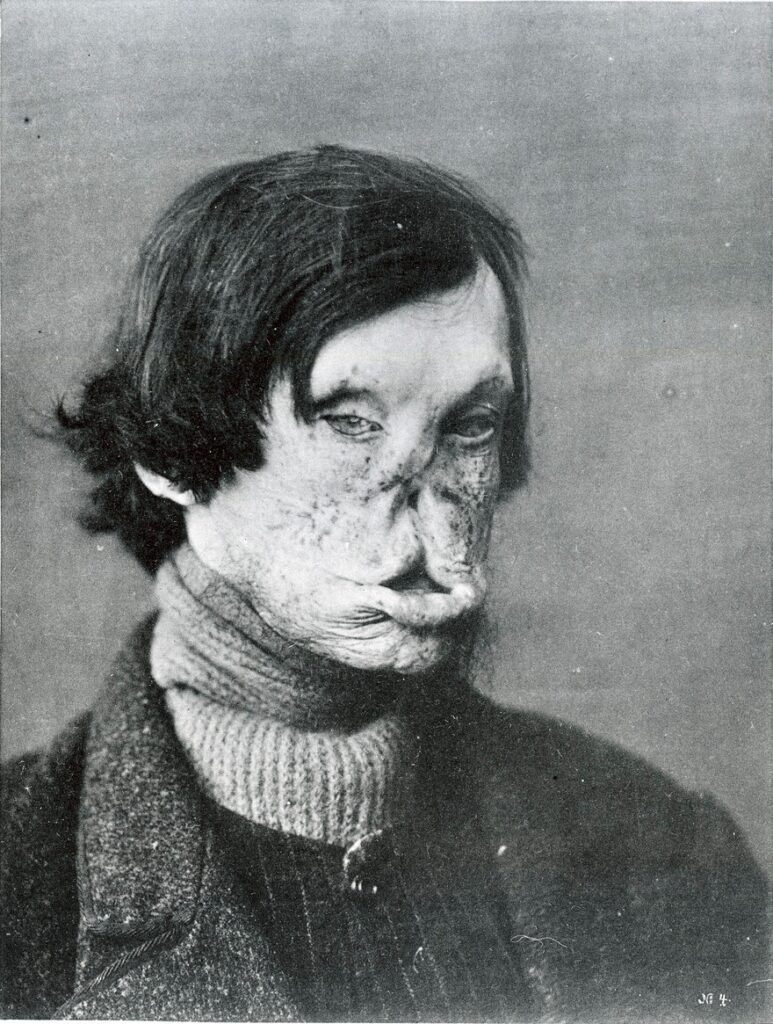

A Horrific Affliction

One reason that leprosy inspired such fear was its disfiguring appearance. While some forms of the disease were relatively mild, such as when the person infected had a strong immune response, it could also present in ways that made the affected person appear quite frightening. Famously, some forms of necrotic leprosy could cause body parts to literally fall off, as nerve damage caused a loss of feeling that meant injuries and infection would often go unnoticed. Sometimes, the septum (the centre part of the nose) would collapse and the nose would become disfigured or even become completely detached. Some cases of nerve damage paralised the facial muscles, causing the face to sag lopsidedly. These physical disfigurations only exacerbated the superstitious beliefs that surrounded the disease, and people suffering from leprosy often received little sympathy.

A Cure in Oil

For several centuries, the only known effective treatment for leprosy was chaulmoogra oil, from a tree native to India and South-East Asia. Though the oil had been used in alternative Eastern medicine for some time, the treatment only entered the Western world in the 19th century, after it was introduced to Europe in 1854 by a professor at Bengal Medical College. However, taking the oil treatment was almost as unpleasant as the disease itself. If swallowed, the oil caused severe nausea, and injections to the skin caused fever and rashes. The oil also was not completely effective, and there was no guarantee of being cured. Despite this and the unwanted side effects, chaulmoogra oil remained the best treatment for leprosy until the 1940s, when antibiotics began to be developed. Promin was the first drug shown to be effective against leprosy by Guy Henry Faget at the National Leprosarium in Carville, Louisiana. The hospital, now known as the Gillis W. Long Hansen’s Disease Center, still houses some patients, and new treatments and vaccines for Hansen’s disease are still being developed today.

Sources and Further Reading

https://web.stanford.edu/class/humbio103/ParaSites2005/Leprosy/history.htm

https://www.healthline.com/health/leprosy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_leprosy

https://www.hrsa.gov/hansens-disease/history.html

Barnett, R., The Sick Rose or; Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration, (London, 2014)