The case of Alphonse Louis is one of the earliest and most famous examples of the use of a prosthetic jaw. Not only was the piece a masterful piece of craftsmanship, it also returned the patient in question to a relatively normal life after he suffered a horrific disfigurement.

War Injuries

Today, most facial prosthetics are used by those who have undergone surgery for tumours. However, until the end of WWII the most common cause of disfigurement was war injuries. As warfare evolved, more powerful weapons meant more horrific injuries, with heavy artillery and the resulting shrapnel making loss of limb and facial disfiguration a very real danger on the battlefield.

During the siege of Antwerp in 1832, Alphonse Louis was hit in the face by a large piece of shrapnel which completely destroyed his lower jaw. Perhaps due to luck and the quick actions of the field surgeon in equal measure, he did not die from the severe injury. However, though Alphonse survived the initial ordeal, he was left with virtually no quality of life. He could no longer eat or talk, and was left constantly drooling as his tongue was left dangling from his throat. However, at the time, even the best surgeons had little idea how to effectively reconstruct an entire jaw, and so a more creative solution had to be found.

An Elegant Solution

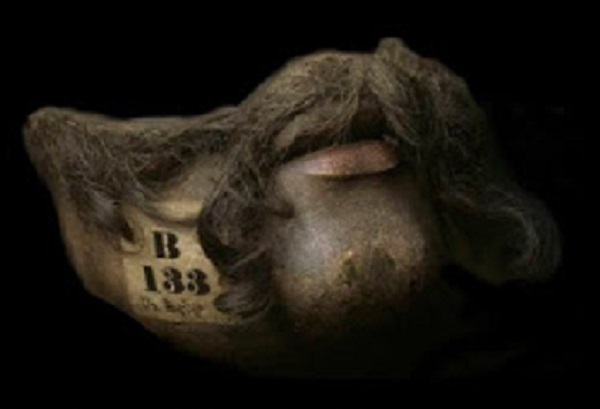

Once it became clear that Alphonse was going to make a full recovery, it was suggested that a mask should be made for him to allow him to have as normal a life as possible. Not only would a prosthetic help to disguise the extent of his injury, but it would also allow him to use his tongue much more easily, enabling him to speak and eat again. A cast was taken of his face, which was passed to a silversmith so that a replacement jaw could be constructed for the injured soldier. The completed silver mask weighed three pounds, and was painted to resemble flesh. It also had a moustache and whiskers made of real hair in order to make it appear as realistic as possible. The mask had a tray that could be emptied of saliva, and the fastenings could be covered by a cravat.

Rehabilitation

Alphonse returned to Lille in 1833. Doctors from the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh reported that when they visited him the day before his departure, he was in high spirits, could talk perfectly clearly, and had even managed to gain weight since his unfortunate injury. Alphonse seemed quite happy to show off his mask, which he was able to take off and adjust one-handed, and was reportedly as proud of it as he was of his medals.

Sources and Further Reading

Strackee, S. D., ‘Mandibular reconstruction revisited; on modeling and fixation techniques of the fibular free flap’, University of Amsterdam, (2004)

Kaufman MH, McTavish J, Mitchell R., ‘The gunner with the silver mask: observations on the management of severe maxillo-facial lesions over the last 160 years’, Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh, (1997) Dec;42(6):367-75