People have always been fascinated by the bizarre and macabre. During the nineteenth century, one of the most popular tourist attractions in Paris was not a famous monument or an art gallery, but the city morgue. At its peak between 1830 and 1864, it boasted of around 40,000 visitors a day as people flocked to see the victims of grisly murders and tragic suicides. Being on the banks of the Seine, drowning victims were particularly common, and the bodies of children often drew the largest crowds.

Practical Purposes

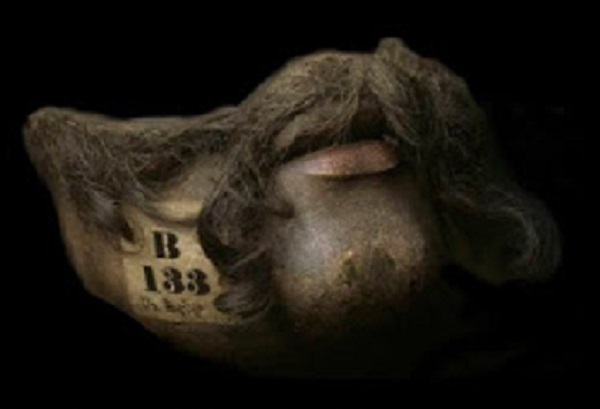

The original intent of the viewing galleries of the city morgue was to allow relatives of missing or deceased persons to identify unclaimed bodies. Bodies were displayed behind a plate glass window, with their clothing (and any other personal effects they may have been found with) hung on a rail above them. Decomposition was slowed by dripping cold water onto the bodies from taps running across the ceiling. As well as putting a name to unidentified corpses, the city morgue also played a role in crime solving. Often, the police would bring murder suspects to the morgue to confront them with their actions, in the hopes of spurring a confession. Indeed, the technique was thought to be so successful that electric lights were introduced to the morgue in 1888 with the sole intention of increasing the effect of the confrontation.

Sensational Media

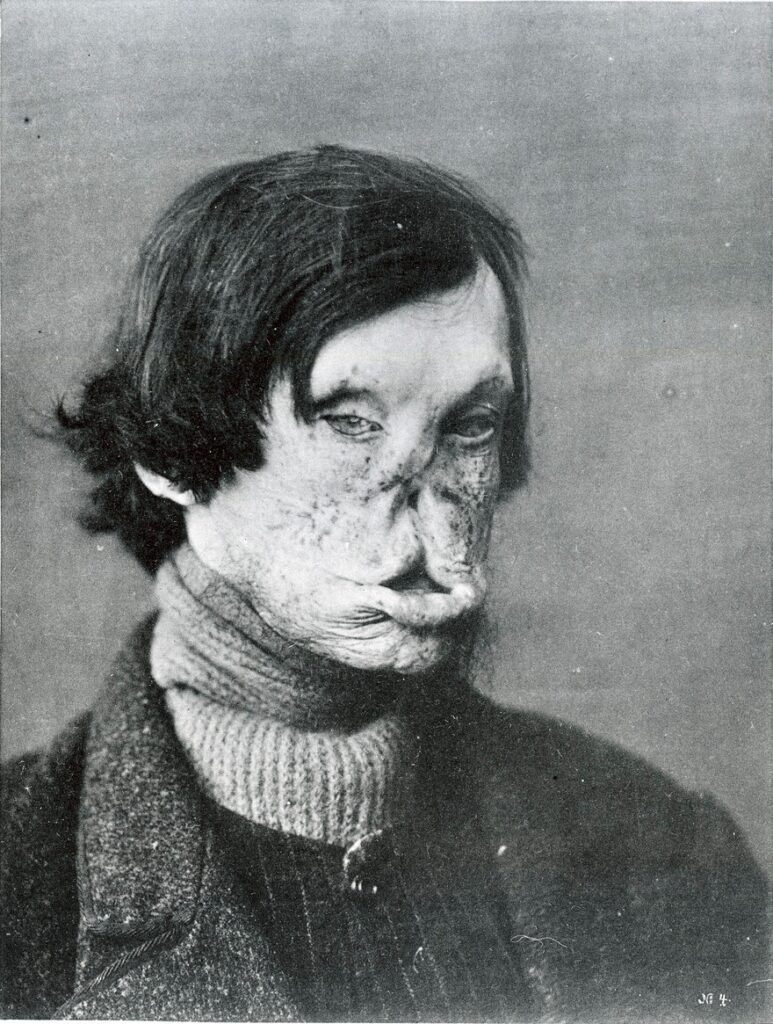

However, the morgue soon developed a reputation as a public spectacle as urban society developed to encompass both mass media and exhibition culture. Newspaper readership grew exponentially during the nineteenth century, and it therefore is unsurprising that stories of industrial accidents and gruesome murders were reported both more often and in even greater detail than ever before. Sensationalist headlines and dramatic speculation not only sold more papers, but also meant that readers would rush to see the bodies of victims at the city morgue. However, these crowds were not necessarily just morbid viewers. Much of the public that formed the huge crowds to be found at the morgue on any given day may have felt a sense of sympathetic solidarity with the unfortunate corpses laid out on the slab, and in many ways helped draw attention to the shocking and often avoidable fates they had suffered.

Display by Design

When the city morgue was relocated in 1864, it was designed with its huge visitor numbers and international repute in mind. Its new location behind the famous Notre Dame cathedral made it easy for even the most directionally-challenged tourist to find, and its opening hours of dawn til dusk seven days a week made it vastly more accessible than any other comparable morgue in Europe. Though death was by no means a stranger to either country, both France and Britain experienced a shifting view of death during the nineteenth century where both death itself and mourning became a far more public and performative phenomenon. The viewing window of the morgue was often compared to that of a department store, and the grim display represented an accessible form of entertainment for both rich and poor alike. The Paris City Morgue closed its doors to the public in 1907, and today most countries have strict laws dictating if and how human remains can be displayed.

Sources and Further Reading

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/paris-morgue-public-viewing

https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/W-RTBBEAAO5mfQ3M

Trednnick, B. “Some Collections of Mortality Dickens, the Paris Morgue, and the Material Corpse.” Victorian Review, vol. 36, no. 1, 2010, pp. 72–88

Shaya, G. “The Flaneur, the Badaud, and the Making of a Mass Public in France, circa 1860-1910.” The American Historical Review, vol. 109, no. 1, 2004, pp. 41–77